Tháng này, chúng tôi có dịp trò chuyện với cô Dung Hứa của Vital Access Care Foundation, hay còn được biết đến với tên Vietnamese American Cancer Foundation – Hội Ung Thư Việt Mỹ. Cô Dung và đội ngũ VACF liên tục làm việc để trợ giúp nhu cầu của cộng đồng người Việt tại Quận Cam, California và các khu vực lân cận. Cô Dung cho chúng tôi biết về các kinh nghiệm trong việc ngăn ngừa bệnh viêm gan B và ung thư gan trong cộng đồng, cũng như sự đóng góp vào chiến dịch Learn the Link, chính thức khởi động vào tháng 2 năm 2024. Cô Dung chia sẻ những thử thách mà mình phải đối mặt, những trải nghiệm quý giá và nhiều cách cô ấy làm việc để kết nối và nâng cao hiểu biết cho cộng đồng.

Chiến dịch Learn the Link được tạo ra nhằm nâng cao nhận thức về mối liên hệ giữa bệnh viêm gan B mãn tính và ung thư gan một cách phù hợp về mặt văn hoá cho các cộng đồng chịu ảnh hưởng nặng nề nhất. Chiến dịch được thông tin thông qua việc trực tiếp nói chuyện với các thành viên trong cộng đồng và được xây dựng với việc tập trung và ưu tiên các nhu cầu của họ. Hepatitis B Foundation – Quỹ Viêm Gan B đã tổ chức các nhóm thảo luận và thành lập một ban cố vấn để tìm hiểu về nhu cầu và lo ngại của cộng đồng, qua đó tạo ra tài liệu tham khảo thích hợp với các nền văn hoá khác nhau.

Cô có thể giới thiệu về bản thân và cơ quan của cô được không?

Tên tôi là Dung và tôi hiện đang làm việc tại Vital Access Care Foundation – Hội Ung Thư Việt Mỹ. VACF vừa chính thức đổi sang tên tiếng Anh mới vì đã mở rộng các dịch vụ không chỉ tập trung vào bệnh ung thư, tuy nhiên chương trình Hướng Dẫn Toàn Vẹn về Ung Thư, và chương trình về Viêm Gan B – Ung Thư Gan vẫn là trọng tâm chính. VACF được thành lập vào năm 1998 và cung cấp các dịch vụ hỗ trợ chung về ung thư, sau này phát triển thành chương trình tập trung vào bệnh ung thư vú. Vào năm 2003, VACF bắt đầu các chương trình về gan và viêm gan B. Một trong những người sáng lập VACF là bác sĩ chuyên khoa ung thư và một người sáng lập khác là bác sĩ chuyên khoa tiêu hoá, hai bác sĩ này giúp tư vấn và hướng dẫn cho chương trình viêm gan B và ung thư gan của VACF.

Cô có thể cho tôi biết về các chương trình của VACF nhằm ngăn ngừa trực tiếp bệnh viêm gan B và ung thư gan không?

Các chương trình về viêm gan B và ung thư gan của VACF tập trung vào cộng đồng người Việt. VACF cung cấp dịch vụ tiếp cận, nâng cao hiểu biết, hướng dẫn bệnh nhân và xét nghiệm truy tầm bệnh. VACF bắt đầu bằng việc phổ biến thông tin vì nhiều người trong cộng đồng không biết về bệnh viêm gan B. VACF tổ chức các buổi truy tầm cho cộng đồng tại nhà thờ và các sự kiện văn hoá. Mọi người thường hay đồng ý làm xét nghiệm khi VACF tổ chức truy tầm ở các sự kiện này. Nếu ai đó xét nghiệm dương tính với viêm gan B, VACF sẽ hướng dẫn và kết nối họ tới dịch vụ chăm sóc. Nếu có ai cần tiêm ngừa, họ sẽ được hướng dẫn đi tiêm ngừa. Nếu gặp phải một trường hợp phức tạp hơn, nhân viên sẽ tham khảo ý kiến một trong những thành viên trong Hội Đồng Quản Trị để có tư vấn chuyên nghiệp miễn phí. Trong thời gian đại dịch, VACF đã liên kết dịch vụ viêm gan B và COVID–19, khuyến khích mọi người tiêm vắc xin COVID-19 và xét nghiệm viêm gan B cùng lúc. VACF đã vận dụng kinh nghiệm tiêm ngừa vắc xin đã có từ trước và rất ngạc nhiên là nhiều người sẵn sàng ‘bị chích” hai lần trong một ngày.

Cô có thể cho tôi biết về cộng đồng mà VACF phục vụ không?

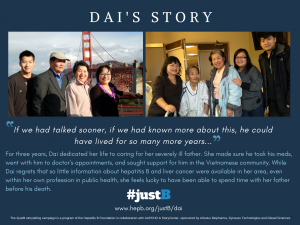

VACF tập trung vào cộng đồng người Mỹ gốc Việt tại Quận Cam. Cộng đồng này bao gồm người nhập cư và người tị nạn. Vẫn còn rất nhiều định kiến xung quanh bệnh viêm gan B trong cộng đồng người Việt ở đây. Nhiều người vẫn tin rằng họ có thể bị nhiễm viêm gan B khi ăn chung với người bị dương tính. Trong cộng đồng người Việt có câu: “Quét nhà thì ra rác”, đây là một thành ngữ lảng tránh, ví dụ như nếu không đi khám bác sĩ, thì sẽ không biết mình bị bệnh. Về mặt văn hoá, thì thường chỉ chia sẻ những điều tốt đẹp. Còn có sự thành kiến xoay quanh việc tìm kiếm sự giúp đỡ. Vì vậy thường không nên chia sẻ về việc bản thân đang gặp khó khăn hoặc bộc lộ sự yếu đuối, điều này có thể khiến người ta chìm đắm trong nỗi đau của bản thân.

Ngoài sự thành kiến, nhiều người còn phải đối mặt với các vấn đề sức khoẻ tinh thần không được chẩn đoán và nhiều khó khăn khi chuyển đến một đất nước mới. Trong cộng đồng, tỷ lệ người có bảo hiểm cũng thấp hơn, dẫn đến việc nhận dịch vụ chăm sóc y tế định kỳ trở nên khó khăn. Cộng đồng người Á Châu cũng phải đối mặt với quan niệm sai lầm về thiểu số mẫu mực, điều này có thể gây hại vì nhiều người cho rằng người Châu Á có bằng cấp cao và thu nhập ổn định, điều này không phải lúc nào cũng đúng.

Nhiều người VACF giúp đỡ chỉ nói một ít tiếng Anh hoặc hoàn toàn không nói tiếng Anh. Khi những người này đến nước Mỹ, họ cần tìm việc làm ngay và thường bị xếp vào nhóm lao động tay nghề thấp. Rất khó để những người nhập cư và tị nạn mới này có thể thăng tiến. Tuy nhiên, nhiều người vẫn có được động lực làm việc bằng cách tạo ra những cơ hội tốt hơn cho gia đình và con cái họ.

Một số thách thức VACF gặp phải trong việc giải quyết các mối lo ngại về sức khoẻ của cộng đồng là gì?

Các thử thách lớn nhất là thành kiến đối với bệnh tật và việc có được tài liệu thích hợp về mặt văn hoá và ngôn ngữ. Ngôn ngữ rất phức tạp. Các làn sóng nhập cư khác nhau ảnh hưởng đến cách giao tiếp với mọi người vì ngôn ngữ thay đổi theo thời gian, do đó việc tìm kiếm sự cân bằng giữa ngôn từ cũ và mới hơn là rất quan trọng. Đây tiếp tục là một quá trình học hỏi đối với tôi vì tôi ngày càng tiếp xúc nhiều hơn với mọi người trong cộng đồng. Việc đối phó với thành kiến và rào cản về ngôn ngữ và văn hoá là quan trọng và khó khăn, nhưng đó cũng là phần đáng quý nhất trong công việc này.

Tại sao cô nghĩ rằng tài liệu tham khảo về bệnh viêm gan B và ung thư gan lại rất quan trọng cho cộng đồng của cô?

Có được các tài liệu là điều quan trọng vì tri thức là sức mạnh. Chìa khoá để làm tốt hơn là sự hiểu biết và kiến thức đến từ việc học hỏi. Mọi người sẽ không biết điều gì là tốt nhất cho mình nếu họ không có đủ thông tin, điều này cần được củng cố thông qua việc lặp đi lặp lại nhiều lần. Nếu mọi người làm việc gì đó mà không hiểu tại sao phải làm vậy thì hành vi đó sẽ không kéo dài. Nhưng nếu họ hiểu, họ có thể tiếp tục những hành vi đó và giúp truyền bá thông tin đến những người khác.

Kinh nghiệm của cô trong việc thực hiện các nhóm thảo luận và phục vụ trong ban cố vấn để cung cấp thông tin về chiến dịch Learn the Link là gì?

Tôi đã có mặt để hỗ trợ và quan sát nhóm thảo luận. Tôi nhớ là các thành viên cộng đồng đã tham gia rất tích cực. Họ có kinh nghiệm cá nhân về bệnh viêm gan, điều này giúp họ có động lực để tham gia nhiệt tình hơn. Đó là một không gian an toàn để họ đóng góp ý kiến. Việc trở thành một phần của quá trình này đã mang lại sức mạnh cho họ và khiến họ cảm thấy được lắng nghe. Nỗ lực của dự án này là nhằm tạo ra các tài liệu phù hợp về mặt văn hoá và tìm kiếm phản hồi từ cộng đồng, qua đó làm mọi người cảm thấy như họ đã đóng góp cho một điều gì đó quan trọng và có ý nghĩa.

Khi phục vụ trong ban cố vấn, tôi nhớ rằng nhóm chúng tôi đã được tập hợp lại từ nhiều cộng đồng khác nhau và chúng tôi đã đưa ra những suy nghĩ và phản hồi về dự án. Tôi đã có cơ hội được nghe những nhu cầu, lo ngại, và ý kiến phản hồi từ những cộng đồng mà VACF thường không làm việc chung. Tôi nhận ra rằng có nhiều điểm tương đồng giữa các cộng đồng khác nhau và thật hữu ích khi có cơ hội tìm hiểu thêm về các cộng đồng khác. Nhìn thấy mọi người đưa ra quan điểm của họ và lắng nghe những điểm tương đồng cũng như đặc trưng là một trải nghiệm thú vị.

Tại sao việc các tổ chức phải nói chuyện trực tiếp với các thành viên cộng đồng khi tạo ra các chiến dịch như “Learn the Link” là quan trọng?

Tập trung vào cộng đồng là điều quan trọng đối với bất kỳ chiến dịch hoặc hoạt động nào. Để giúp đỡ cho cộng đồng, chúng ta phải lắng nghe họ. Chúng ta không muốn tạo ra thứ gì đó mà chúng ta cho là tốt nhất nhưng lại không phù hợp với những người mà lẽ ra nó phải phù hợp với. Sự kết nối và mối quan hệ trực tiếp mang đến cho các thành viên cộng đồng một cảm giác thoải mái khi chia sẻ ý kiến là chìa khoá để thành công trong việc tiếp cận và nâng cao nhận thức.

Cách hiệu quả nhất để các tổ chức tương tác với cộng đồng của cô là gì?

Cách hiệu quả nhất để tương tác với cộng đồng là gặp gỡ họ ở những nơi họ thường lui tới. Sẵn sàng đi ra ngoài và tìm kiếm các thành viên cộng đồng, và cởi mở để hiểu biết nhu cầu cũng như nỗi lo của họ là điều quan trọng. Chúng ta không thể chỉ làm việc trong khung giờ bình thường từ 9 giờ sáng đến 5 giờ chiều, mà phải ra ngoài và tìm hiểu cộng đồng ở ngoài giờ làm việc thông thường. VACF cố gắng linh hoạt trong giờ giấc để gặp gỡ các thành viên cộng đồng, tổ chức các buổi họp mặt vào cuối tuần, ở chùa hoặc công viên. Chúng tôi cố gắng lắng nghe, thấu hiểu và xây dựng mối quan hệ bền vững.

Hiểu được sự khác biệt về văn hoá và giữa các thế hệ cũng rất quan trọng. Đặc biệt đối với người Việt, lời truyền miệng có sức mạnh rất lớn. Thông tin lan truyền trong cộng đồng thông qua việc truyền miệng có thể lan truyền như cháy rừng.

Kết nối với các nhà lãnh đạo cộng đồng, những người và tổ chức đang làm việc trực tiếp với cộng đồng là một cách khác để kết nối với mọi người. Điều này bắt nguồn từ hoàn cảnh nhập cư và tị nạn; những người trải qua chiến tranh có thể khó tin tưởng hơn vào các cơ quan chính quyền nhưng lại tin tưởng vào những người mà họ đã xây dựng mối quan hệ tốt với.

Cô có suy nghĩ hoặc nhận xét nào khác về chiến dịch “Learn the Link” và tiềm năng của nó trong việc cải thiện các hoạt động chăm sóc sức khoẻ của người dân trong cộng đồng của cô không? Có tài liệu nào khác mà cô hy vọng sẽ thấy trong tương lai không?

Tôi đã xem qua các tài liệu khi chúng được phổ biến và đã chia sẻ tài liệu cho một nhân viên mới xem, và tôi thấy rằng tất cả các tài liệu đều bằng tiếng Anh. Khi tất cả các bản dịch đều có sẵn, sẽ thật tuyệt khi có thể chia sẻ không chỉ với cộng đồng mà còn với những người làm việc với cộng đồng nữa. Viêm gan B có thể không phải ưu tiên hàng đầu của mọi người, nhưng với sự quảng bá, những tài liệu này có thể nhắc nhở mọi người rằng kẻ giết người thầm lặng này vẫn tồn tại và có sẵn các nguồn hỗ trợ khi họ cần đến.

Kinh nghiệm của cô trong việc giúp đánh giá và chỉnh sửa một trong những bản thảo khoa học cuối trước khi nó được gửi đi để xuất bản từ dự án này là gì?

Có rất nhiều thông tin để đọc! Việc tham dự các buổi họp cố vấn, tham dự các nhóm thảo luận, và đọc bản thảo đã được chia ra thực hiện trong một khoảng thời gian dài. Rất thú vị khi được đọc bản tóm tắt tất cả những công việc đã được hoàn tất. Đó là một cơ hội tốt để ôn lại kiến thức và tôi cũng thích đọc những câu trích dẫn đã để lại cho bản thân mình ấn tượng sâu sắc. Các cộng đồng khác có nhiều điểm chung với cộng đồng người Việt, cho nên rất tuyệt khi được hợp tác cùng nhau vì tất cả chúng ta đều cùng đang cùng làm công việc ý nghĩa này.

Click here to read the original blog post in English.