Understanding the hepatitis B virus and the panel of blood tests needed to determine infection or immunity can be a stressful and challenging task. In simplest terms, “hepatitis” means liver inflammation and the hepatitis B virus can ultimately cause liver inflammation. The liver is an important organ in the human body and responsible for the removal of toxins and regulation of digestion (learn more about the function of the liver here). The hepatitis B virus can infect and disrupt critical functions of the liver in supporting your overall health.

How the hepatitis B virus works

In the case of the hepatitis B virus, the host is the liver cell. As the virus makes more copies of itself, the liver may become damaged, and sometimes it is unable to carry out its essential tasks to regulate metabolism, nutrients, and digestion. It is best to prevent hepatitis B infections when we can – and since antibodies are the best defense against the virus, the hepatitis B vaccine can be used to signals the body to make antibodies to fight the virus. The hepatitis B vaccine provides lifelong protection from the virus. However, this is only possible before infection with the virus. If somebody is already infected with the virus, antiviral therapy is used to control the virus and prevent liver damage – antiviral medications disrupt the life cycle of the virus by disabling viral receptors from binding to liver cells.

Blood test panel to diagnose hepatitis B:

The only way to tell someone’s hepatitis B status is through a panel of blood tests – the tests are all done at one time, and only one small tube of blood is needed. These tests are not included in routine testing, so it is important to ask your doctor to test you for hepatitis B or try to find a free screening event near you (http://www.hepbunited.org/). The panel consists of the following tests to determine your hepatitis B status:

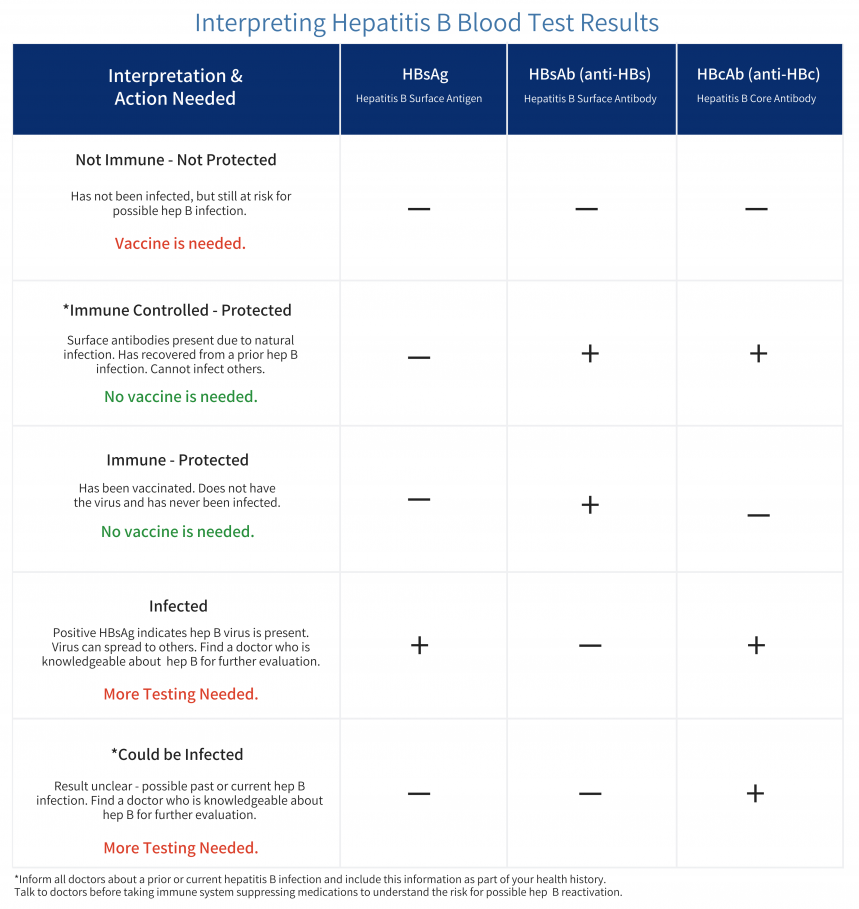

- HBsAg:

- This tests for the hepatitis B surface antigen in someone’s blood. The surface antigen is the protein that surrounds the virus and protects it from attack by the host. A positive surface antigen test indicates that the virus is present in the body. A “positive” or “reactive” result for HBsAg indicates that someone is infected with hepatitis B and can transmit the virus to others.

- HBsAb

- This tests for the hepatitis B surface antibody in someone’s blood. The surface antibodies are produced by the immune system and can fight off the virus by attaching to the surface antigen protein. This test can detect the presence of these antibodies. Ideally this test will be ordered quantitatively (numerically). A “positive” surface antibody test (meaning numbers reading >10 IU/mL) means that a person has protection against the hepatitis B virus (either by vaccine or from a past exposure).

- HBcAb (total)

- This is known as the hepatitis B core antibody test. The core antibody is produced by the immune system after infection with the virus. This test indicates an existing or past infection of the hepatitis B virus.

To learn more about interpreting your test results, click here.

Important things to know about Hepatitis B Core Antibody (HBcAb)

Someone who has markers of past infection, particularly hepatitis B core antibody, can be at risk for hepatitis B reactivation. Reactivation can be triggered by immunosuppressive therapies and cause significant life-threatening challenges. If you test HBcAb+, please talk to your doctor about what that means, and make sure you notify all future health care providers.

How is reactivation with HBV defined?

Reactivation is defined as the sudden increase or reappearance of HBV (hepatitis B virus) DNA. When the virus invades the cell, it forms a covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) in the nucleus of infected cells referred to as hepatocytes. Because cccDNA is resistant to antiviral treatments, it is never removed from the cells. Therefore, even after recovery from a past infection, the cccDNA is present and may reactivate. It is not clearly understood why this may happen, but certain factors may increase the risk for reactivation.

To learn more about the core, click here.

What puts one at risk for reactivation?

- Virologic factors such as high baseline HBV DNA, hepatitis B envelope antigen positivity (HBeAg), and chronic hepatitis B infection that persists for more than 6 months.

- Detectable HBV DNA levels and detectable levels of HBsAG can increase the risk for HBRr (reactivation)

- Testing positive for HBeAg also increases the risk for reactivation

- Co-infection with other viruses such as hepatitis C or hepatitis Delta

- Older age

- Male sex

- Cirrhosis

- An underlying condition requiring immunosuppressive therapies (rheumatoid arthritis, lymphoma, or solid tumors)

- Certain medications can increase the likelihood of reactivation by more than 10%.

- B-cell depleting agents such as rituximab, ofatumumab, doxorubicin, epirubicin, moderate or high-dose corticosteroid therapy lasting more than 4 weeks.

How to prevent reactivation of hepatitis B

Hepatitis B reactivation is a serious condition that can lead to health complications, Reactivation is avoidable if at-risk individuals are identified through screening. Current guidelines recommend that individuals at the highest risk (those receiving B-cell depleting therapies and cytotoxic regimens) should receive antiviral therapies as prophylaxis before beginning immunosuppressive therapy. These antiviral therapies should also be continued well beyond stopping the immunosuppressive therapies. Be sure to talk to your doctor to be sure you are not at risk for reactivation.

References

Hepatitis b virus reactivation: Risk factors and current management strategies.

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus: A review of Clinical Guidelines.

https://aasldpubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cld.883

https://www.hepb.org/prevention-and-diagnosis/diagnosis/understanding-your-test-results/