Being diagnosed with hepatitis B can be a confusing experience and may leave you with many questions. Understanding your diagnosis is essential for your health, and understanding how hepatitis B is transmitted can help prevent transmission to others.

How is it Spread?

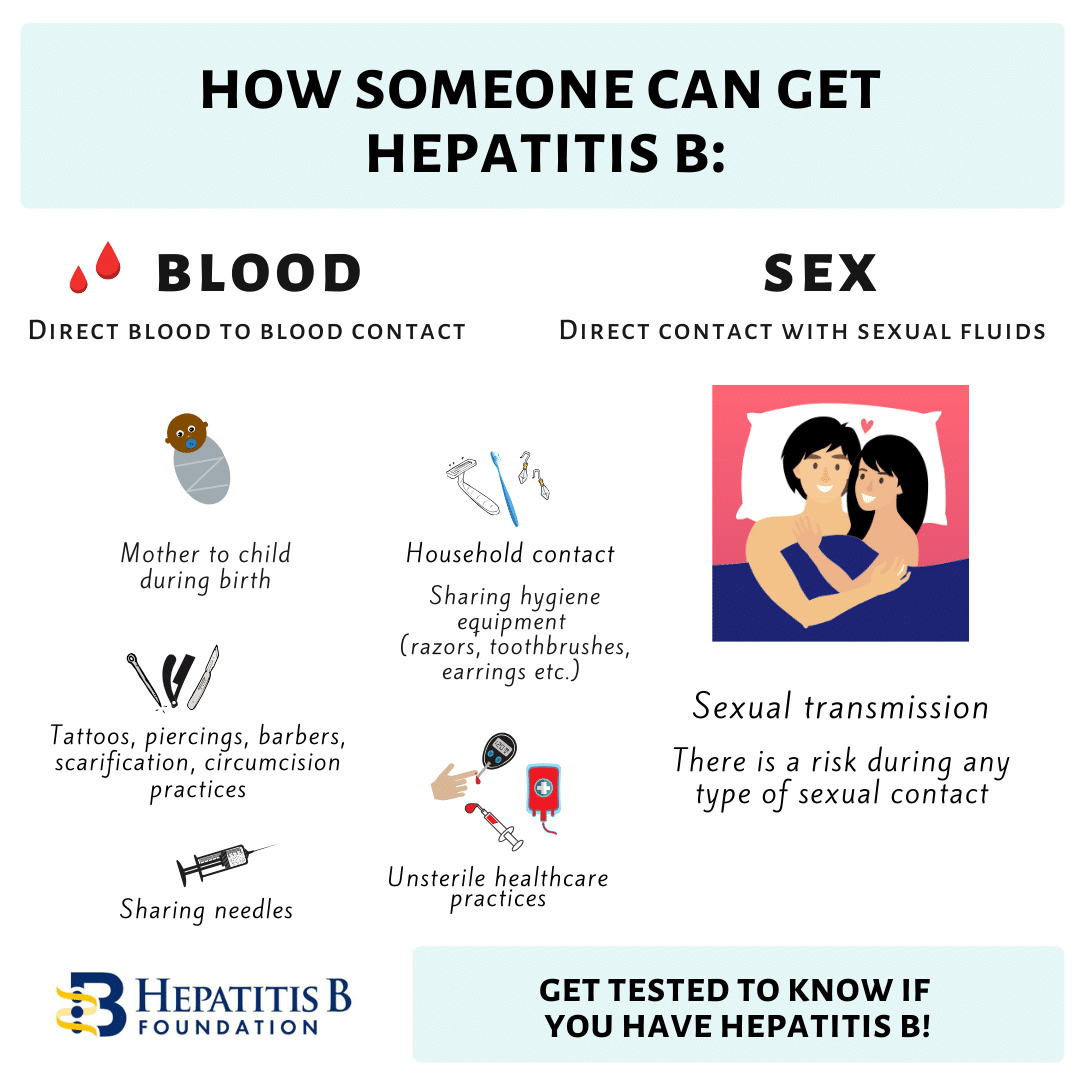

Hepatitis B is transmitted through direct contact with infected blood. This can happen through direct blood-to-blood contact, unprotected sex, unsterile needles, and unsterile medical or dental equipment. Globally, hepatitis B is most commonly spread from an infected mother to her baby due to the blood exchange during childbirth. It can also be transmitted inadvertently by the sharing of personal items such as razors, toothbrushes, nail clippers, body jewelry, and other personal items that have small amounts of blood on them.

Hepatitis B is not transmitted casually by sneezing or coughing, shaking hands, hugging or sharing or preparing a meal. In fact, hepatitis B is not contracted during most of life’s daily activities. You don’t need to separate cups, utensils, or dishes. You can eat a meal with or

Most of those who are newly infected have no notable symptoms. This is why it is important to encourage family members and sexual partners to get tested if you test positive. Often, it remains undetected until it is caught in routine blood work, blood donation, or later in life after there is liver inflammation or disease progression.

Dealing with a Possible Exposure:

One important factor for those that may have been exposed is the timing. There is a 4-6 week window period between an exposure to hepatitis B and when the virus shows up in the blood (positive HBsAg test result). If you go for immediate testing, please understand that you will need to be re-tested 9 weeks later to confirm whether or not you have been infected. It is essential to practice safe sex and follow general precautions until everyone is sure of their status –both the known and potentially infected.

You may still be in a waiting period trying to determine if you are acutely or chronically infected. It is possible that you have not had symptoms with your hepatitis B. It’s also very likely you are unsure as to when you were infected. Not knowing the details of your infection can be stressful and confusing, but the most important thing to do now is to educate yourself so that you can take the proper steps to protect your liver and prevent transmission.

Preventing Future Transmission:

- Always cover open wounds. Keep cuts, bug bites – anything that bleeds or oozes – covered with a bandage. It’s also a good idea to carry a spare bandage.

- Be sure to practice safe sex (use a condom) until you are sure your partner has completed their hepatitis B vaccine series. Be aware that multiple sex partners and non-monogamous relationships can expose you to the potential of more health risks and even the possibility of a co-infection, so it is best to use a condom. Co-infections are when someone has more than one serious chronic condition (like HBV and HCV , HBV and HIV or HBV and HDV). Co-infections are complicated health conditions that you want to avoid. Therefore, practice safe sex by using a latex or polyurethane condom if you have multiple partners.

- Keep personal items personal. Everyday items that are sharp may contain small amounts of blood. This includes things like razors, nail clippers, files, toothbrushes and other personal items where microscopic droplets of blood are possible. This is good practice for everyone in the house. Simple changes in daily habits keep everyone safe!

If a person has been tested and their results show that they are not already vaccinated or have not recovered from a past infection, then they should start the series as soon as possible. This includes sexual partners and close household contacts and family members. The HBV vaccine is a safe and effective 2 or 3-shot series.

If you wish to confirm protection, the timing of the antibody titre test should be 4-8 weeks following the last shot of the series. If titers are equal to or above 10 mIU/mL, then there is protection for life. If someone has been previously vaccinated a titer test may show that their titers have waned and dipped below the desired reading. There is no reason to panic, as a booster shot can be administered and then a repeated titer test 1-2 months later can ensure adequate immunity. Once you know you have generated adequate titers, there is no need for concern of transmission!

When recovering from an acute infection, if your follow up blood test results read: HBsAg negative, HBcAb positive and HBsAb positive then you have resolved your HBV infection and are no longer infectious to others and you are no longer at risk for infection by the HBV virus again.

However if your follow up blood tests show that you are chronically infected or your infection status is not clear, you will want to take the precautionary steps to prevent transmitting your HBV infection to others. You will also need to talk to your doctor to be sure you have the appropriate blood work to determine your HBV status and whether or not you are chronically infected.

Please be sure to talk to your doctor if you are unsure, and don’t forget to get copies of all of your lab results!

On the other hand, hepatitis B begins as a short-term infection, but in some cases, it can progress into a chronic, or life-long, infection. Chronic hepatitis B is the world’s leading cause of liver cancer and can lead to serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. Most adults who become infected with hepatitis B develop an acute infection and will make a full recovery in approximately six months. However, about 90% of infected newborns and up to 50% of young children will develop a life-long infection. This is because hepatitis B can be transmitted from an infected mother to her baby due to exposure to her blood. Many infected mothers do not know they are infected and therefore cannot work with their physicians to take the necessary

On the other hand, hepatitis B begins as a short-term infection, but in some cases, it can progress into a chronic, or life-long, infection. Chronic hepatitis B is the world’s leading cause of liver cancer and can lead to serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis or liver cancer. Most adults who become infected with hepatitis B develop an acute infection and will make a full recovery in approximately six months. However, about 90% of infected newborns and up to 50% of young children will develop a life-long infection. This is because hepatitis B can be transmitted from an infected mother to her baby due to exposure to her blood. Many infected mothers do not know they are infected and therefore cannot work with their physicians to take the necessary  With five different types of viral hepatitis, it can be difficult to understand the differences between them. Some forms of hepatitis get more attention than others, but it is still important to know how they are transmitted, what they do, and the steps that you can take to protect yourself and your liver!

With five different types of viral hepatitis, it can be difficult to understand the differences between them. Some forms of hepatitis get more attention than others, but it is still important to know how they are transmitted, what they do, and the steps that you can take to protect yourself and your liver!  that their primary mode of transmission is through direct blood-to-blood contact with an infected person. Also, both hepatitis B and C can cause chronic, lifelong infections that can lead to serious liver disease. Hepatitis B is most commonly spread from mother-to-child during birth while hepatitis C is more commonly spread through the use of unclean needles used to inject drugs.

that their primary mode of transmission is through direct blood-to-blood contact with an infected person. Also, both hepatitis B and C can cause chronic, lifelong infections that can lead to serious liver disease. Hepatitis B is most commonly spread from mother-to-child during birth while hepatitis C is more commonly spread through the use of unclean needles used to inject drugs.