Mongolia is one of the world’s most sparsely populated countries yet is home to the highest infection rates of hepatitis B and delta coinfection worldwide1. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 5-10% of the nearly 300 million global hepatitis B patients are co-infected with hepatitis delta. Hepatitis delta is the most severe form of viral hepatitis, and greatly increases the risk of cirrhosis, scarring of the liver, and liver cancer; with seven out of 10 patients progressing within 10 years 4. In Mongolia, 70% of hepatitis B patients are coinfected with hepatitis delta, and the country is known for having the highest rates of liver cancer on the planet2,3. These statistics are startling and highlight a public health crisis for Mongolia, where most families have at least one family member affected 2.

How are people getting infected?

Historically, healthcare-related exposures are suspected to be the biggest risk for contracting hepatitis in Mongolia. Despite the 1993 national policy was set to regulate the multi-use of single-use syringes in healthcare settings, effective sterilization practices, and medical staff training, proper inspections remain an ongoing issue. Healthcare workers themselves are also at risk, with requirements for hepatitis B vaccination set by the Ministry of Health recently in 20145. Although routine infant vaccination for hepatitis B began in 19916, older populations remain at risk or are susceptible to exposures.

Treatment Access

For a nation so widely affected by liver disease, as of 2015, skilled physicians and liver transplant experts are sparse – with only one reported team performing transplants in Ulaanbaatar, the capital city1. Fibroscan, CT scans, and liver biopsies; routine screening tools for liver disease and liver cancer, have only been introduced in recent years, and are still not routinely used for liver cancer screening as recommended by WHO7. This lack of surveillance leaves most patients to endure late diagnoses. Due to the rural landscape, where nearly 30% of the population lives below the poverty line10 and historically nomadic lifestyle accessing care is a challenge. Access to treatment for hepatitis B is additionally a challenge, and traditional medicines might be utilized. Pegylated interferon, the only current and somewhat effective treatment for hepatitis B and delta coinfection, was registered about 10 years ago in Mongolia and is still not covered by its national healthcare system, making it too expensive for most low and middle-income families8. With the help of partnerships, the government has integrated funding for palliative care for liver cancer patients, with most facilities centralized around the capital city7. With a failing insurance system and little government prioritization for prevention and treatment, many are calling on the World Health Organization (WHO), pharmaceutical companies and NGOs to step in to curb the crisis9.

Hope

Mongolia’s crisis has not been left unaddressed. Over the last 10 years, Mongolia’s government has prioritized combatting hepatitis, developing its first viral hepatitis national strategy in 2010, and focusing on prevention, affordable treatment, and public awareness programs. Admirably, coverage under the national insurance plan for antivirals began in 2016, greatly subsidizing the cost of hepatitis B treatment11. These efforts did not go unnoticed, and in 2018, WHO praised Mongolia’s efforts in moving towards the elimination of hepatitis B and C, recognizing its successes in its national program, “Whole-Liver Mongolia”. Another program, “Hepatitis Free Mongolia”, an initiative of the Flagstaff International Relief Effort (FIRE), Flagstaff Rotary Club, Rotary Club of Ulaanbaatar and the WHO, offers free hepatitis education, screening, vaccination and care for those infected. The project also trains healthcare providers and offers free exams, diagnostic services and patient counseling; a vital service for many who may not be able to access or afford these services otherwise. Since 2011, the project, along with FIRE’s Love the Liver program have tested nearly 9,000 people for hepatitis B, screened 6,000 for liver cancer and performed over 3,000 specialist exams, and, in a country of only 3 million people, has made a meaningful impact. The effort is also unofficially supported by Mongolia’s Ministry of Health, who is continually investing in efforts to curb the burden of hepatitis.

References:

1. “Viral Hepatitis in Mongolia: Situation and Response.” World Health Organization, 2015, iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/13069/9789290617396_eng.pdf.

2. “Hepatitis: A Crisis in Mongolia.” World Health Organization, 2017, www.who.int/westernpacific/news/feature-stories/detail/hepatitis-a-crisis-in-mongolia.

3. Rizzetto, Mario. (2016). The adventure of delta. Liver International. 36. 135-140. 10.1111/liv.13018.

4. Abbas, Z., Abbas, M., Abbas, S., & Shazi, L. (2015). Hepatitis D and hepatocellular carcinoma. World journal of hepatology, 7(5), 777–786.

5. Baatarkhuu, Oidov & Uugantsetseg, G & Munkh-Orshikh, D & Naranzul, N & Badamjav, S & Tserendagva, Dalkh & Amarsanaa, J & Young, Kim. (2017). Viral Hepatitis and Liver Diseases in Mongolia. Euroasian Journal of Hepato-Gastroenterology. 7. 68-72. 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1215.

6. Davaalkham, Dambadarjaa & Ojima, Toshiyuki & Uehara, Ritei & Watanabe, Makoto & Oki, Izumi & Wiersma, Steven & Nymadawa, Pagbajab & Nakamura, Yosikazu. (2007). Impact of the Universal Hepatitis B Immunization Program in Mongolia: Achievements and Challenges. Journal of epidemiology / Japan Epidemiological Association. 17. 69-75. 10.2188/jea.17.69.

7. Alcorn, Ted. (2011). Mongolia’s struggle with liver cancer. Lancet. 377. 1139-40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60448-0.

8. “Country Programme on Viral Hepatitis Prevention and Control.” World Health Organization, Western Pacific Region, 2015, www.wpro.who.int/mongolia/mediacentre/releases/20160318_viral_hep_prevention_control/en/.

9. Jazag, A., Puntsagdulam, N., & Chinburen, J. (2012). Status quo of chronic liver diseases, including hepatocellular carcinoma, in Mongolia. The Korean journal of internal medicine, 27(2), 121–127. 10. “Poverty in Mongolia.” Asian Development Bank, 2019, www.adb.org/countries/mongolia/poverty.

11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on a National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C; Strom BL, Buckley GJ, editors. A National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C: Phase Two Report. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017 Mar 28. 1, Introduction. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK442230

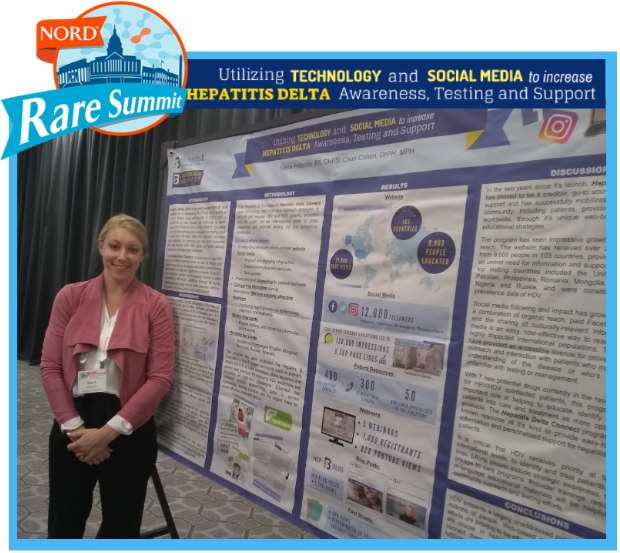

NORD through participating in rare disease Twitter chats and presenting a poster at the NORD Rare Action Summit in October 2018. We’re very excited to be a part of the coalition, and to be spreading awareness about hepatitis delta!

NORD through participating in rare disease Twitter chats and presenting a poster at the NORD Rare Action Summit in October 2018. We’re very excited to be a part of the coalition, and to be spreading awareness about hepatitis delta!

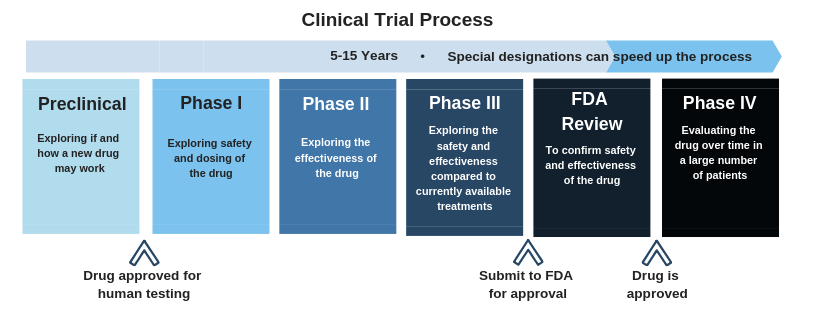

Phase 3 clinical trials have been announced for two drugs,

Phase 3 clinical trials have been announced for two drugs,  Click here

Click here

What is the standard treatment for hepatitis delta and how long is it taken?

What is the standard treatment for hepatitis delta and how long is it taken? Although there are no standard guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis delta, pegylated interferon has been shown to be effective for some patients. It is usually administered via weekly injections for 1 year or more and is able to cure roughly 15-40% depending on the length of time that treatment is administered. Although many patients see declines in their hepatitis delta virus levels, most do not maintain long-term control following the conclusion of treatment.

Although there are no standard guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis delta, pegylated interferon has been shown to be effective for some patients. It is usually administered via weekly injections for 1 year or more and is able to cure roughly 15-40% depending on the length of time that treatment is administered. Although many patients see declines in their hepatitis delta virus levels, most do not maintain long-term control following the conclusion of treatment.

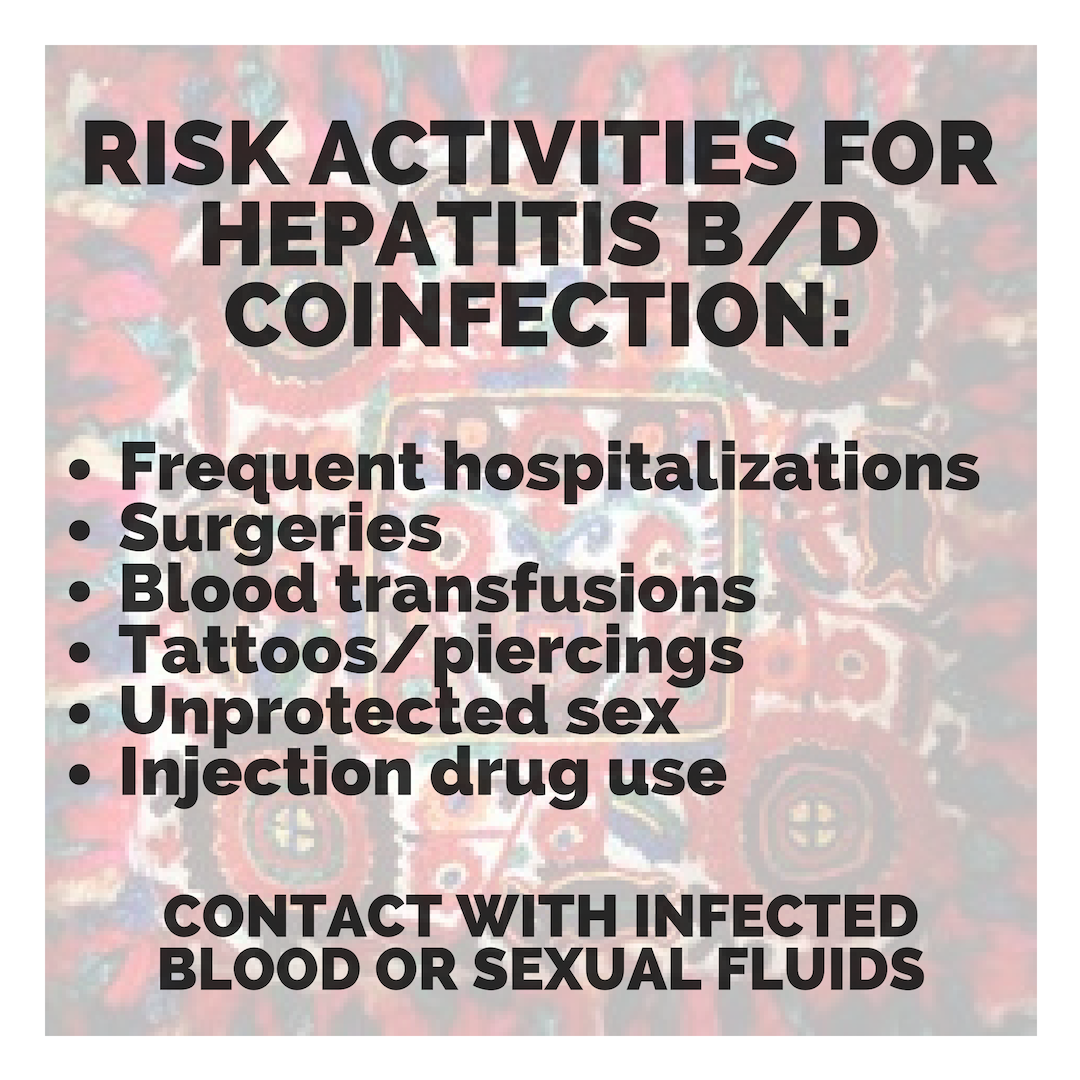

disease.1,3. Additionally; lack of hepatitis B vaccination recommendations for high risk groups, low implementation of hepatitis B screening during pregnancy, supply shortages and vaccine hesitancy, have created opportunities for hepatitis B and D transmission. Exposure to infected blood or sexual fluids through blood transfusions or surgeries (before the 1990’s), tattoos, piercings, injection drug use, or sexual contact with an infected person, can expose people already living with hepatitis B to hepatitis D, or expose those who have not received the full hepatitis B vaccine series to both viruses. Control of hepatitis B and D coinfection has also been hindered by the lack of a national registry and surveillance system thus preventing an understanding of the accurate prevalence and public health burden1.

disease.1,3. Additionally; lack of hepatitis B vaccination recommendations for high risk groups, low implementation of hepatitis B screening during pregnancy, supply shortages and vaccine hesitancy, have created opportunities for hepatitis B and D transmission. Exposure to infected blood or sexual fluids through blood transfusions or surgeries (before the 1990’s), tattoos, piercings, injection drug use, or sexual contact with an infected person, can expose people already living with hepatitis B to hepatitis D, or expose those who have not received the full hepatitis B vaccine series to both viruses. Control of hepatitis B and D coinfection has also been hindered by the lack of a national registry and surveillance system thus preventing an understanding of the accurate prevalence and public health burden1. which has led to late diagnoses and cost many patient lives. For patients who are diagnosed, investigational testing is not covered by the national insurance house, placing a financial burden on patients to pay out of pocket for the additional testing necessary to manage their coinfection. With pegylated interferon injections as the only semi-effective treatment option, even diagnosed patients struggle to effectively control their coinfection and even less are connected to clinical trials. Although there are 7 new drugs in clinical trials, progress has lagged behind patient need for new therapies, many of whom are living with cirrhosis.

which has led to late diagnoses and cost many patient lives. For patients who are diagnosed, investigational testing is not covered by the national insurance house, placing a financial burden on patients to pay out of pocket for the additional testing necessary to manage their coinfection. With pegylated interferon injections as the only semi-effective treatment option, even diagnosed patients struggle to effectively control their coinfection and even less are connected to clinical trials. Although there are 7 new drugs in clinical trials, progress has lagged behind patient need for new therapies, many of whom are living with cirrhosis.