Each year in September, the Hepatitis B Foundation recognizes National African Immigrant and Refugee HIV and Hepatitis Awareness Day (NAIRHHA). Founded by advocates in Massachusetts, Washington D.C., and New York, NAIRHHA Day has been observed annually on September 9th by healthcare professionals, awareness campaigns, and other organizations since 2014. Although not yet nationally recognized, the multicultural AIDS Coalition (MAC) and the Coalition Against Hepatitis B for People of African Origin (CHIPO) are working to establish NAIRHHA day as its own federally designated awareness day. As explained by Chioma Nnaji, Director at the Multicultural AIDS Coalition’s Africans For Improved Access (AFIA) program, there is a great need to establish NAIRHHA day as its own day. “Several of the current awareness days are inclusive of African immigrant communities, but do not comprehensively address their unique social factors, cultural diversity as well as divergent histories and experiences in the US.”

Why NAIRHHA Day?

People born outside of the U.S. often face different health challenges than those born in the country and face various barriers to accessing important healthcare services. African immigrants (AI) are disproportionately burdened by  HIV and viral hepatitis. Advocates for NAIRHHA Day recognized the need to address these health issues in the community and thought that a combined awareness day would be the most effective way to reach the largest number of people impacted.

HIV and viral hepatitis. Advocates for NAIRHHA Day recognized the need to address these health issues in the community and thought that a combined awareness day would be the most effective way to reach the largest number of people impacted.

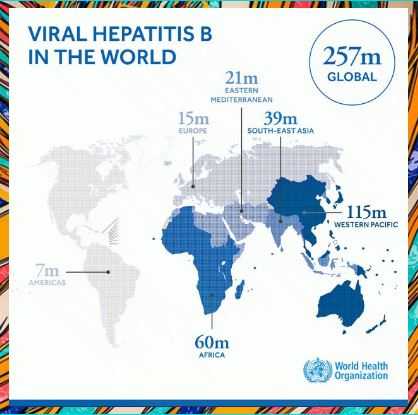

Hepatitis B presents a significant public health burden for many African countries, and subsequent immigrant populations living in the United States. Although data is limited on hepatitis B infection among African immigrant (AI) and refugee communities in the U.S., studies have shown infection rates are high – between 5 and 18%1,2,3,4,5. One community study in Minnesota even found AIs accounting for 30% of chronic hepatitis B infections 6. AI communities are also known to be disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS, with diagnosis rates six times higher than the general U.S. population7. Despite this alarming disparity, HIV and hepatitis B awareness, prioritization, and funding has remained limited for this population.

Two of the largest barriers to testing for HIV and viral hepatitis among African immigrants are lack of awareness and stigma. Cultural and religious values shape the way people view illness, and there can be fears around testing and diagnosis of illness, and moral implications for why someone may feel they are at risk. While stigma about HIV/AIDS and hepatitis B often come from within one’s own community and culture, it is primarily driven by lack of awareness. Oftentimes, awareness is low in an individual’s home country because of limited hepatitis education, resources, and healthcare infrastructure. When they arrive in the U.S., awareness remains low for similar reasons. Community health workers and physicians are vital stakeholders to raise community awareness in a culturally sensitive way to help identify current infections and prevent future ones through vaccination.

Recognizing NAIRHHA Day is important in order to address the numerous barriers to prevention and treatment that African immigrants face. It was also founded to acknowledge the cultural and ethnic differences that influence how African-born individuals interact with their medical community and the concept of illness. The specific goals of the day of recognition include:

- Raising awareness about HIV/AIDS and viral hepatitis to eliminate stigma;

- Learning about ways to protect against HIV, viral hepatitis and other related diseases;

- Taking control by encouraging screenings and treatment, including viral hepatitis vaccination;

- Advocating for policies and practices that promote healthy African immigrant communities, families, and individuals.

What has been done so far?

The path to federal recognition has been a slow process, but progress has been made! Check out the timeline below for a brief overview of what has been accomplished since the day was created:

2014:

-

- Inaugural city-wide events in Houston, Texas; Boston, Massachusetts; Washington D.C.; Maryland; Seattle, Washington; New York; Ohio and Philadelphia.

- A national petition was created and 40% of the petitioners are from or live in Massachusetts; 60% of signers are from 33 other states across the US

2015:

-

- Social Media efforts reached more than 500,000 individuals

- NAIRHHA Day toolkit was developed and disseminated

2016:

-

- Senator Elizabeth Warren gave a proclamation in Massachusetts

- Created an informational blog post for the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable

- Joined the African immigrant Hepatitis/HIV Twitter chat (#AIHHchat)

2017:

-

- Hosted a national webinar focused on barriers and strategies addressing HIV and hepatitis B among African immigrants

- Official request to HIV.gov to officially recognize NAIRHHA Day

2018:

-

- Hosted an online panel discussion addressing HIV and HBV stigma among African immigrant

- New social media campaign

- National Webinar with HBF and CHIPO focused on stigma

September marks the unofficial beginning of National African Immigrant Heritage Month (NAIHM) – state and federal officials in over thirty states recognize September as NAIHM despite it not being federally declared – which is why NAIRHHA Day is held on September 9th. Federal recognition would significantly boost awareness within the community and allow for the creation of much-needed resources like culturally sensitive education tools. It would also help to disseminate the important health messages on a larger, national scale.

This year, the Hepatitis B Foundation and CHIPO are excited to be sponsoring four community events with partners throughout the U.S. to commemorate NAIRHHA day and promote hepatitis B and HIV education and testing in AI communities.

For more information about NAIRHHA Day:

- Follow NAIRHHA Day on Twitter @NAIRHHA

- Check out our blog posts on NAIRHHA Day

- Visit the CHIPO website and click here for downloadable badges and infographics

- Contact Chioma, Director of the Multicultural AIDS Coalition, at cnnaji@mac-boston.org to get involved in advocacy for NAIRHHA Day

References:

- Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, Roberts H, Brosgart CL. (2012). Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology, 56(2), 422-433. And Painter. 2011. The increasing burden of imported chronic hepatitis B—United States, 1974-2008. PLoS ONE 6(12): e27717.

- Chandrasekar, E., Song, S., Johnson, M., Harris, A. M., Kaufman, G. I., Freedman, D., et al. (2016). A novel strategy to increase identification of African-born people with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the Chicago metropolitan area, 2012-2014. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E118.

- Edberg, M., Cleary, S., & Vyas, A. (2011). A trajectory model for understanding and assessing health disparities in Immigrant/Refugee communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(3), 576-584.

- Kowdley, K. V., Wang, C. C., Welch, S., Roberts, H., & Brosgart, C. L. (2012). Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign‐born persons living in the united states by country of origin. Hepatology, 56(2), 422-433.

- Ugwu, C., Varkey, P., Bagniewski, S., & Lesnick, T. (2008). Sero-epidemiology of hepatitis B among new refugees to Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(5), 469-474.

- Kim WR, Benson JT, Therneau TM, Torgerson HA, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3d. Changing epidemiology of hepatitis B in a U.S. community. Hepatology 2004;39(3):811–6.

- Blanas, D. A., Nichols, K., Bekele, M., Lugg, A., Kerani, R. P., & Horowitz, C. R. (2013). HIV/AIDS among African-born residents in the United States. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 15(4), 718–724.

covered medications, or

covered medications, or  safety and importance of vaccines. NIAM was established by the

safety and importance of vaccines. NIAM was established by the

Meng, Representative Judy Chu, Senator Tammy Duckworth, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Representative Ilhan Omar!

Meng, Representative Judy Chu, Senator Tammy Duckworth, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Representative Ilhan Omar! Congressional Reception to share some inspiring words!

Congressional Reception to share some inspiring words! partners across the nation!

partners across the nation!  our partners & passersby to help #FindTheMissingMillions!

our partners & passersby to help #FindTheMissingMillions!