By Christine Kukka

By Christine Kukka

Another way to become infected is if someone infected with chronic hepatitis B is exposed to someone with hepatitis D. This is called a superinfection, and in 90 percent of cases, people with chronic hepatitis B will also develop chronic hepatitis D.

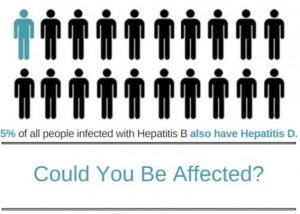

Who is at risk of hepatitis D? Anyone with chronic hepatitis B who themselves or their family comes from Sub-Saharan Africa, China, Russia, Middle East, Mongolia, Romania, Georgia, Turkey, Pakistan and the Amazonian River Basin should be tested. Hepatitis D rates in some of these countries can reach up to 30 percent in people infected with chronic hepatitis B.

What medical conditions suggest hepatitis D? Anyone with chronic hepatitis B who is not responding to antiviral treatment, or who has signs of liver damage even though they have a low viral load (HBV DNA below 2,000 IU/mL) should be tested. Fatty liver disease (caused by obesity) and liver damage from alcohol or environmental toxins should be ruled out before testing for hepatitis D.

Often, people with hepatitis D have low viral loads (even if they are hepatitis B “e” antigen HBeAg-positive), but they have signs of liver damage, including elevated liver enzyme (ALT/SGPT) levels.

Do hepatitis B antivirals work against hepatitis D? No. The hepatitis D virus (HDV) is structurally different from the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and does not respond to tenofovir and entecavir used to treat hepatitis B. Hepatitis B antivirals will lower HBV DNA, but they don’t reduce HBsAg, which HDV need to thrive and reproduce.

How is hepatitis D treated? The only proven hepatitis D treatment is pegylated interferon. Interferon cures hepatitis D 15 to 25 percent of the time after one year of treatment. Once interferon clears hepatitis D, doctors treat patients who continue to be infected with HBV with antivirals. There are dozens of research companies now looking into hepatitis D treatment, and if researchers can find a cure for hepatitis B that eradicates HBsAg, it will also be effective against hepatitis D.

How should people with hepatitis D be monitored? According to Dr. Gish, doctors should:

- Monitor patients’ ALT/SGPT and liver function at least every six months

- Perform an ultrasound of the liver and conduct a liver cancer biomarker panel (including AFP, AFPL3% and DCP) every six months;

- And, perform viral load (HBV DNA) and HDV RNA testing every six months.

How is hepatitis D prevented? The hepatitis B vaccine prevents hepatitis D infection, as does use of safe sex and safe injection practices. According to Dr. Gish, all hepatitis B-positive pregnant women should be tested for hepatitis D if they or their families are from a country with high rates of hepatitis D, or if they have signs of liver damage — even if they do not come from a region with high hepatitis D rates.

If a pregnant woman is infected with either hepatitis B and/or hepatitis D, immunizing her newborn with the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine within 12 hours of birth and giving the baby a dose of HBIG (hepatitis B antibodies) will prevent both infections.

Bottom line, if you are infected with chronic hepatitis B, you should be tested for hepatitis D if:

- You or your family comes from a region with high rates of hepatitis D; and/or

- You have a low viral load, but you continue to have signs of liver damage, indicated by elevated ALT/SGPT or an ultrasound exam of your liver, if your doctor has ruled out fatty liver, NASH or alcohol-related liver damage.

Talk to your doctor about getting tested. Click here for a hepatitis D fact sheet to give to your doctor and click here for a patient-oriented fact sheet. An affordable hepatitis D test has recently become available in the U.S. For more information, click here.