What is the standard treatment for hepatitis delta and how long is it taken?

What is the standard treatment for hepatitis delta and how long is it taken?

Although there are no standard guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis delta, pegylated interferon has been shown to be effective for some patients. It is usually administered via weekly injections for 1 year or more and is able to cure roughly 15-40% depending on the length of time that treatment is administered. Although many patients see declines in their hepatitis delta virus levels, most do not maintain long-term control following the conclusion of treatment.

Although there are no standard guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis delta, pegylated interferon has been shown to be effective for some patients. It is usually administered via weekly injections for 1 year or more and is able to cure roughly 15-40% depending on the length of time that treatment is administered. Although many patients see declines in their hepatitis delta virus levels, most do not maintain long-term control following the conclusion of treatment.

Can pregnant hepatitis delta patients be treated with interferon?

Can pregnant hepatitis delta patients be treated with interferon?

Interferon has not been proven to be safe for administration during pregnancy and should not be administered. It may be harmful to the baby.

Interferon has not been proven to be safe for administration during pregnancy and should not be administered. It may be harmful to the baby.

What is the best way to manage a hepatitis delta infection during pregnancy, if interferon cannot be used?

What is the best way to manage a hepatitis delta infection during pregnancy, if interferon cannot be used?

A liver specialist may continue to manage the hepatitis B infection during pregnancy through antiviral treatment. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends antiviral treatment during the third trimester of pregnancy for women with high hepatitis B viral loads.

A liver specialist may continue to manage the hepatitis B infection during pregnancy through antiviral treatment. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends antiviral treatment during the third trimester of pregnancy for women with high hepatitis B viral loads.

How can hepatitis B and delta transmission be prevented to the baby?

Because a hepatitis B infection is required for someone to become infected with hepatitis delta, transmission from mother to child can be prevented with the hepatitis B vaccine. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend the first dose within 12 hours of birth, along with and a dose of HBIG (hepatitis B immunoglobulin), followed by the additional 2 vaccine shots; one at 1 month and the final one at 6 months old. The vaccine, along with HBIG and hepatitis B antiviral treatment (if necessary) greatly reduce the risk of transmission to the baby. In resource-limited countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth, followed by the additional shots on the recommended schedule. Once the vaccination series is completed, the baby should be protected for life against hepatitis B and delta.

If hepatitis delta cannot be treated during pregnancy, do most women have progression of their liver disease during pregnancy?

If hepatitis delta cannot be treated during pregnancy, do most women have progression of their liver disease during pregnancy?

While some women may see progression of their liver disease, due to the relative short length of pregnancy, most women do not show clinical signs of advancing liver disease.

While some women may see progression of their liver disease, due to the relative short length of pregnancy, most women do not show clinical signs of advancing liver disease.

What treatment should follow delivery?

What treatment should follow delivery?

Following delivery, the mother may resume interferon treatment as long as she is not breastfeeding. Interferon treatment while breastfeeding could be harmful to the baby. As for all patients, keeping up-to-date on the latest hepatitis delta clinical trials could provide access to new, experimental treatments that may be more effective. For a global list of clinical trials for hepatitis delta, visit the clinicaltrials.gov web page.

Following delivery, the mother may resume interferon treatment as long as she is not breastfeeding. Interferon treatment while breastfeeding could be harmful to the baby. As for all patients, keeping up-to-date on the latest hepatitis delta clinical trials could provide access to new, experimental treatments that may be more effective. For a global list of clinical trials for hepatitis delta, visit the clinicaltrials.gov web page.

It is very important for all pregnant women who are hepatitis B and delta positive to be managed by a liver specialist who is familiar with managing coinfected patients. For assistance in locating a specialist near you, please visit our Physician Directory page. For additional questions, please visit www.hepdconnect.org or email connect@hepdconnect.org.

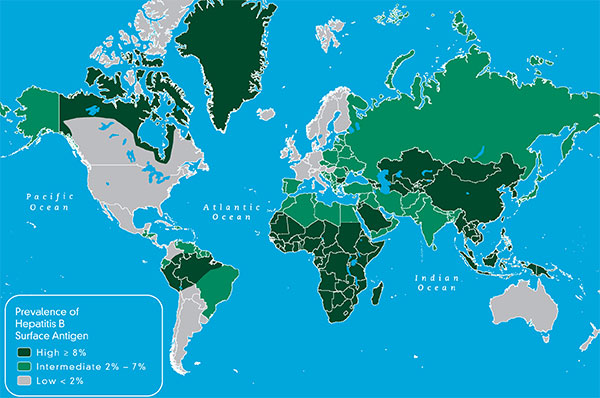

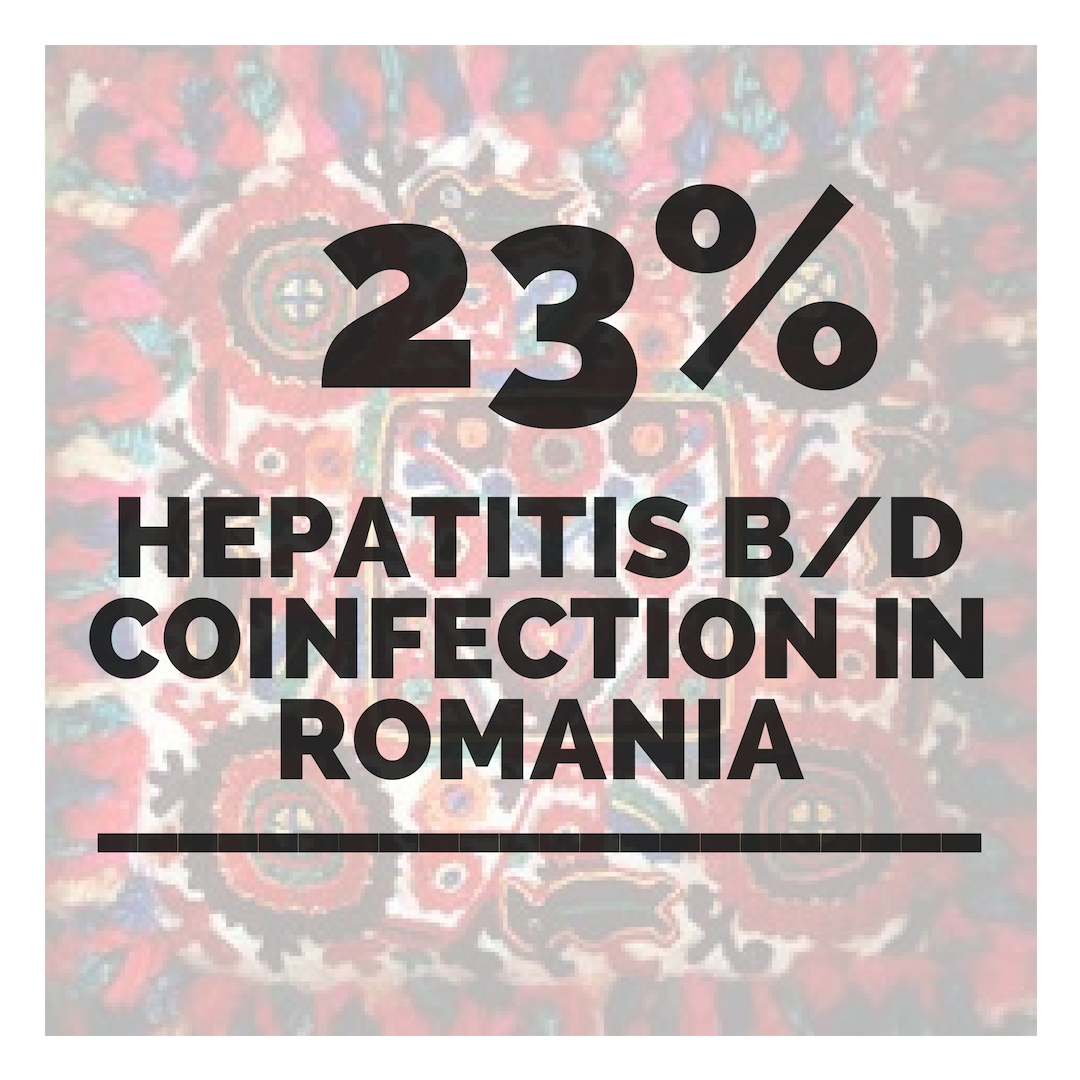

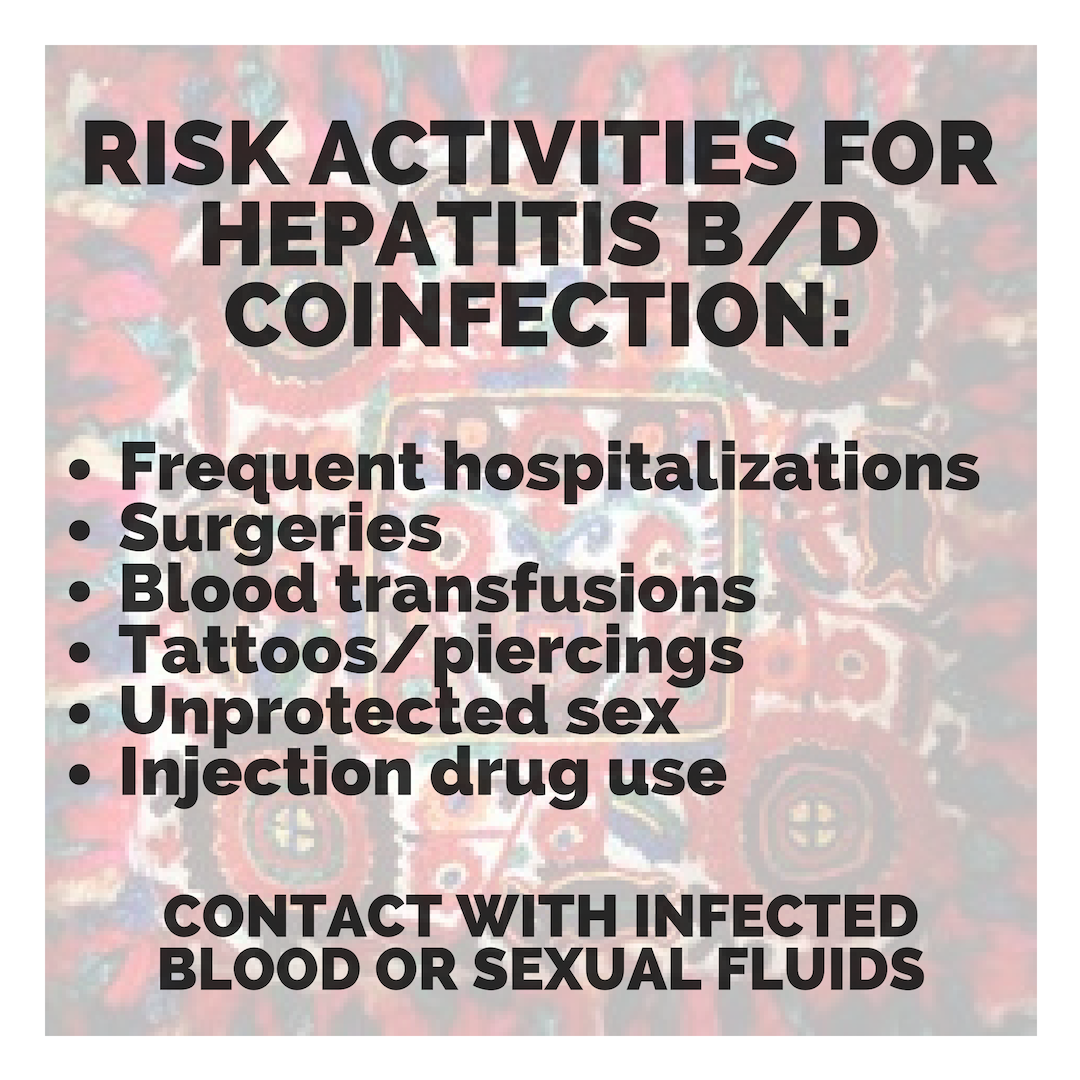

disease.1,3. Additionally; lack of hepatitis B vaccination recommendations for high risk groups, low implementation of hepatitis B screening during pregnancy, supply shortages and vaccine hesitancy, have created opportunities for hepatitis B and D transmission. Exposure to infected blood or sexual fluids through blood transfusions or surgeries (before the 1990’s), tattoos, piercings, injection drug use, or sexual contact with an infected person, can expose people already living with hepatitis B to hepatitis D, or expose those who have not received the full hepatitis B vaccine series to both viruses. Control of hepatitis B and D coinfection has also been hindered by the lack of a national registry and surveillance system thus preventing an understanding of the accurate prevalence and public health burden1.

disease.1,3. Additionally; lack of hepatitis B vaccination recommendations for high risk groups, low implementation of hepatitis B screening during pregnancy, supply shortages and vaccine hesitancy, have created opportunities for hepatitis B and D transmission. Exposure to infected blood or sexual fluids through blood transfusions or surgeries (before the 1990’s), tattoos, piercings, injection drug use, or sexual contact with an infected person, can expose people already living with hepatitis B to hepatitis D, or expose those who have not received the full hepatitis B vaccine series to both viruses. Control of hepatitis B and D coinfection has also been hindered by the lack of a national registry and surveillance system thus preventing an understanding of the accurate prevalence and public health burden1. which has led to late diagnoses and cost many patient lives. For patients who are diagnosed, investigational testing is not covered by the national insurance house, placing a financial burden on patients to pay out of pocket for the additional testing necessary to manage their coinfection. With pegylated interferon injections as the only semi-effective treatment option, even diagnosed patients struggle to effectively control their coinfection and even less are connected to clinical trials. Although there are 7 new drugs in clinical trials, progress has lagged behind patient need for new therapies, many of whom are living with cirrhosis.

which has led to late diagnoses and cost many patient lives. For patients who are diagnosed, investigational testing is not covered by the national insurance house, placing a financial burden on patients to pay out of pocket for the additional testing necessary to manage their coinfection. With pegylated interferon injections as the only semi-effective treatment option, even diagnosed patients struggle to effectively control their coinfection and even less are connected to clinical trials. Although there are 7 new drugs in clinical trials, progress has lagged behind patient need for new therapies, many of whom are living with cirrhosis.

By Sierra Pellechio, Hepatitis Delta Connect Coordinator

By Sierra Pellechio, Hepatitis Delta Connect Coordinator