With Veterans Day comes reports about the lack of adequate mental health care for men and women returning from war. There is another, invisible health issue threatening veterans of all ages–hepatitis B.

Few veterans have ever been screened or treated for hepatitis B though their infection rate is four-times the national average.

The percentage of veterans infected with hepatitis B may actually be higher, but no one knows. Only 15 percent of U.S. veterans have ever been screened for hepatitis B. Among the few screened and diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B, only 25 percent have received antiviral treatment and only 13 percent have been screened for liver cancer.

“While other chronic viral infections, such as hepatitis C and HIV, have received tremendous educational efforts,” said researcher David E. Kaplan, MD, “hepatitis B has received far less attention.” Kaplan and a team of Veterans Administration and University of Pennsylvania researchers authored the study that found woefully inadequate screening and treatment for veterans with hepatitis B.

The veterans’ experience of inadequate hepatitis B screening and care is not uncommon in the U.S. Repeated studies find that in the private sector, a large percentage of people with chronic hepatitis B also never get the monitoring and drugs treatment they.

It’s inexcusable that our flawed civilian health care system does not provide proper hepatitis B treatment, and it’s reprehensible that the VA system that knows many of its patients have hepatitis B and C renders such inadequate care.

About 10 percent of all veterans treated by the Veterans Administration Health Administration today have hepatitis C, and at least 35 percent of them are co-infected with hepatitis B. Recent recruits may be immunized against hepatitis B, but millions who fought in earlier conflicts were not and are now infected.

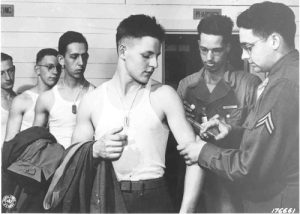

Veterans’ high hepatitis B infection rate should surprise no one. The virus is transmitted through re-used syringes (think of the “jet gun” vaccine administration of earlier eras), exposure to blood and body fluids during injuries in the field, sexual transmission, and shared injecting drug devices. Fifteen percent of servicemen in Vietnam injected heroin.

There are far more documented studies about hepatitis C in veterans than hepatitis B, but these studies provide a snapshot of the risk factors that lead to both infections. Of hepatitis C-positive veterans, about 63 percent are Vietnam veterans and 18.2 percent served after Vietnam.

A recent study searched 2.5 million veterans’ health records between 2002 and 2014 to look for hepatitis B testing and what happened after vets tested positive for the liver infection. Not only were veterans rarely screened for hepatitis B, those who tested positive were rarely referred to treatment despite signs of liver damage.

- The VA screened only 22 percent of veterans who appeared to be at risk of hepatitis B during 2013.

- Of the 50,109 veterans who tested positive for hepatitis B between 2002 and 2014, only 60 percent of veterans who needed treatment for liver damage actually received some kind of treatment. Only a small percentage of those with chronic hepatitis B were screened for liver cancer.

- Among the veterans diagnosed with hepatitis B, the average age was 53, 46.6 percent were white, and 31.4 percent were African-American.

Today, between 65 to 75 percent of the 5 million Americans infected with the hepatitis B and C do not know they are infected. Many of them are veterans who depend only on the VA for medical care. By not screening or treating veterans for hepatitis B, the VA is failing to identify a real enemy that continues silently to infect and kill.