“We will long remember Ted Slavin as a gallant man who loved life and who contributed greatly to our research efforts”

-Baruch S. Blumberg, Irving Millman, W. Thomas London, and other members of the Division of Clinical Research Fox Chase Cancer Center, 19851

“Who is Ted Slavin? Why haven’t I heard about him before?” crept into my mind as I was reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Rebecca Skloot wrote a short snippet about Ted Slavin, detailing the story of a hemophiliac who sold his antibodies and aided Dr. Baruch Blumberg in the discovery of the link between the hepatitis B virus and liver cancer, which eventually led to the first hepatitis B vaccine.2 I was surprised that I had never heard of him, and that his name was not enshrined on the walls of the Hepatitis B Foundation. I see the smiling and jovial face of Dr. Blumberg nearly every time I walk into the office, but never the image of a man who contributed so much to his efforts.

Ted Slavin developed antibodies against hepatitis B after receiving infected blood transfusions to treat his hemophilia. The blood he received back in the 1950s was not screened for any diseases. His doctor helped him realize that his blood was valuable because of the copious amounts of antibodies for hepatitis B. At the time, those antibodies were a hot commodity as scientists were conducting research to learn more about hepatitis B prevention and treatment. Slavin decided to the sell his antibody-rich blood and even donated his blood to Dr. Blumberg’s research team at Fox Chase Cancer Center. He later formed Essential Biologicals, a company that collected blood from others like him. They were everyday patients who could turn their rare or unique blood into money making products, while at the same time advancing important research into diseases that were not well understood.2

As I read the brief overview of Slavin’s life, I initially perceived him as someone who was both lucky and smart: Slavin was lucky because his doctor gave him information on the value of his antibodies2; and smart because he knew how to make the best of something once considered a burden in his life.3 As I did a little more detective work, I realized Ted Slavin was not just a guy who made money off his cells, but someone who contributed to the fight against the hepatitis B virus, which I am passionate about!

My detective work led me to a deeper understanding of Mr. Slavin and his contribution to important milestones on the road to hepatitis B elimination.3,4,5,6,7 I found discussions and case studies on the ethics associated with his circumstance. Through my research journey, I learned more about him and my perception of Slavin started to change. He was, like many, struggling to make ends meet. He didn’t entirely profit off his antibodies because he donated a majority of the money he made to advance scientific research.4 At the same time, Slavin was “hopeful for a cure,” and he trusted Dr. Blumberg, his favorite researcher among the many studying hepatitis B, with his antibodies.1 To Dr. Blumberg and the researchers working with him, Ted Slavin was a brave, courageous man who helped save millions of lives.1

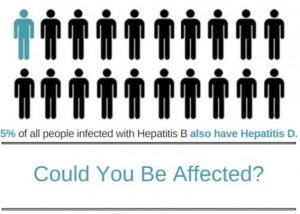

The story of Ted Slavin, like that of Henrietta Lacks, is not only a reminder of the importance of bioethics and the need for public health and scientific research; his story reminds us there is an invisible face behind every success. Because of Ted Slavin, there are tests to diagnose hepatitis B, ways to detect liver cancer linked to hepatitis B, and the first cancer preventative vaccine!

For more information about the hepatitis B vaccine, please visit our website here.

For helping looking for the hepatitis B vaccine, you can go here or to the HealthMap Vaccine Finder.

References:

- Lavin, EFS. (2013). Exploring Life and Death at the Cellular Level: An Examination of How Our Cells Can Live Without Us. Quadrivium: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Scholarship, 5(1),

- Skloot, R. (2010). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Crown Publishing Group.

- Ted Slavin’s Story and more. Retrieved from: http://tissuerights.weebly.com/ted-slavin.html

- Skloot, R. (2006, Apr 16). Taking the Least of You. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/16/magazine/taking-the-least-of-you.html

- Angsana T. (2010, Nov 9). Second Story from Ted Slavin. Retrieved from: http://angsanat.blogspot.com/2010/11/second-story-from-ted-slavin.html

- C, Anna. (2012, Jul 26). World Hepatitis Day: The History of the Hepatitis B Vaccine. Retrieved from: http://advocatesaz.org/2012/07/26/world-hepatitis-day-the-history-of-the-hepatitis-b-vaccine/

By Christine Kukka

By Christine Kukka